Greg Freiherr has reported on developments in radiology since 1983. He runs the consulting service, The Freiherr Group.

Why Politics (and Money) Will Define the Next Generation of Scanners

Photo courtesy of Pixabay

It’s been a long time since radiology focused just on the detection of disease. And it will never see those days again.

Since the serendipitous discovery of X-rays’ ability to reveal what is otherwise hidden, radiological devices have evolved with improved sensitivity and specificity, and the need to meet increasingly “practical considerations,” euphemisms that allude to money.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) rises above such considerations, looking just at efficacy when reviewing medical devices for marketing in the U.S. Similarly the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) base coverage decisions on the proven clinical value of medical devices. But cost is creeping into, some might say even storming the gates of, medical practice.

Legislators are looking for ways to rein in costs associated with Medicare and Obamacare. Consequently the realization is taking hold that medicine must become more efficient and effective. Soon.

In this new reality, ease-of-use plays a central role, streamlining workflow in ways that cut costs and shrink the time from door to treatment. If future research demonstrates improved patient outcome, increased efficiency will have achieved a healthcare hat trick.

Baby Steps

While it is easy to see individual steps in this journey, it is more difficult to see where they are leading. In radiology, clearly the direction is toward a new generation of scanners that continue the journey beyond the traditional focus of finding disease to one that addresses the continuum of patient care.

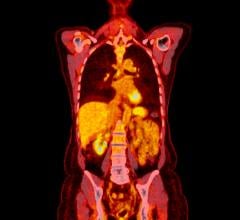

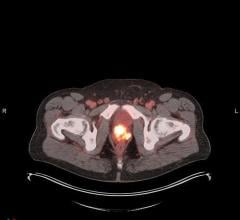

Of course, diagnosis will continue to be a big part of radiology’s mission. But therapy assessment and planning will take on added weight. We are already headed in this direction, as seen in steps taken over the last 15 years with the hybridization of positron emission tomography (PET) and computed tomography (CT), single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and CT, and most recently PET and magnetic resonance (MR). In each, efficiency in patient management, particularly patient prognosis and therapy assessment, has been the overriding consideration. And molecular imaging is not alone.

This directional change is evident in all branches of imaging — the flat panel digitalization of radiography, fluoroscopy, mammography, angiography and cardiac cath; the extension of CT into functional analysis via spectral imaging; the automation of ultrasound and MR — notable in ultrasound for efforts designed to deliver results that are less operator dependent and, therefore, more reproducible; in MR for the standardization of protocols depending on patient habitus and the suspected or proven disease being investigated.

Driving this change are forces that have come not from engineering labs but rather the fiscal recesses of this country’s political system, and their roots extend much deeper than Uncle Sam’s pocket book. Simply put, the U.S. is running out of fiscal options to stimulate its economy. An aging workforce threatens its ability to grow the economy enough to offset its ballooning debt. At the same time the cost of healthcare, particularly in Medicare, threatens to apply added heft to this debt load.

Conflicting Forces Align

On the one hand, the longevity of America’s workforce must be extended. On the other, healthcare costs must be controlled. The confluence of these two seemingly contrary demands — one based on generating revenue, the other on absorbing it — is creating the political will to take action. As has happened before, the political will to implement change has defined imaging technology. But what’s coming will dwarf what has been.

In the past, the political power behind women’s health led to widespread screening with mammography and the adoption of digital technologies spurred by specially crafted reimbursement rates. Might a surge of interest in men’s health, spurred by the need to extend the utility of the aging American workforce, have a similar — but much further ranging — effect on the adoption and development of technologies that address prostate cancer?

Any such effect will barely hint at what is already happening on a much more expansive scale, the embrace of value medicine. Foreshadowed by isolated efforts at patient comfort and outcome, financial considerations have proven to be the determining factors for what is shaping up to be an overhaul of medical practice in this country and the technologies that serve it.

What we are seeing now and will see more of in the near future is testament to the extraordinary power of political forces. As the 21st century unfolds, it is very likely that political will, and the financial need to exercise it, will decide what the next generation of imaging scanners will do and when they will do it.

Editor’s note: This is the third blog in a series of four by industry consultant Greg Freiherr on Where Molecular Imaging Fits in Managing the Cancer Patient. To read the first blog, “How to Achieve the Quantitative Promise of PET/CT,” click here. To read the second blog, “Why the Use of PET/CT in Radiation Therapy Requires Thinking Outside the Box,” click here.

July 30, 2024

July 30, 2024