Greg Freiherr has reported on developments in radiology since 1983. He runs the consulting service, The Freiherr Group.

Thinking Inside the Box

Hard to believe 18 years have passed since I dropped into the engineering lab of Diasonics Ultrasound, a visit brought to mind today by the unveiling half way around the world of another advance in diagnostic ultrasound. That visit and today’s announcement in Vienna, Austria, at the World Federation for Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology demonstrate what ultrasound has become and, for the foreseeable future, will continue to be.

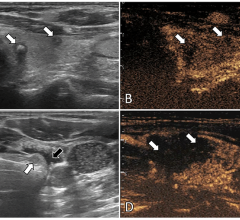

In that Milpitas, Calif., lab in 1993, I saw strewn across a workbench the prototype of the ultrasound industry’s first vascular road-mapping product. Until then, vascular sonography had processed just the frequency of sound waves. This technology, dubbed UltrasoundAngio, processed the amplitude of sound waves to create static images of blood perfusion.

The team at Diasonics had done what others in the industry would soon hustle to replicate. They had found a way to process otherwise unused data to create images unlike any ever made with ultrasound. Over the next two decades, this would become a familiar reprise.

Later development of tissue harmonics would increase signal-to-noise so much that the details of pathologies previously unseen would become crystal clear. Those images came from processing higher frequencies – the harmonics – produced when ultrasound pulses go through body tissue…signals that previously had not been captured.

Shearwave elastography with its palpating virtual finger of sound added a new wrinkle to the face of ultrasound, compressing tissues for an instant so that conventional ultrasonic imaging could gauge tissue elasticity. Because malignant tissues are stiffer than healthy ones, shearwave elastography raises the prospect of helping to assess the breast, prostate, liver and other organs for cancer. This potential, and the possibility that elasticity may indicate other disease states as well, are still being studied, as ultrasound technology continues to advance, repeating this pattern of thinking not outside the box, but in.

Supersonic Imagine, the French pioneer of shearwave elastography, today unveiled technology that combines color flow imaging and pulsed wave Doppler, producing what the company says are color flow clips with 10 times the frame rate of conventional color Doppler. This new product, dubbed UltraFast Doppler, also quantifies the Doppler data.

Peter Burns, a professor of medical biophysics at the University of Toronto, says the advance is clinically significant in two ways. First, it has the speed to reveal pathology in arterial imaging that would otherwise be obscured by aliasing artifacts. Second, it speeds workflow by combining the pulsed Dopper and color flow acquisitions.

So it is that this latest wrinkle adds to the character of diagnostic ultrasound, which has progressed beyond the easy pickings of its youth. With maturity has come iterative development and improvement that find value in what has been overlooked and what has yet to be combined.

July 19, 2024

July 19, 2024