Greg Freiherr has reported on developments in radiology since 1983. He runs the consulting service, The Freiherr Group.

Nuc Med Promises HIV Cure

My generation has seen the rise of a frightening kind of STD, one that was unflinchingly lethal early on and since has been unrelenting, if survivable. Today AIDS is managed, not cured, the lethality of its cause, HIV, held at bay with a cocktail of daily medications. But now there is hope for a cure: radioimmunotherapy (RIT) promises the destruction of HIV-infected cells and the means to verify it.

Researchers at Albert Einstein College of Medicine have used RIT to kill cells infected with HIV. They were destroyed in the blood samples of patients treated with a retroviral antibody. Optimism rising from the in vitro work has been bolstered by in vivo studies on mice, according to Ekaterina (Kate) Dadachova, Ph.D., who says clinical studies are scheduled to begin soon. “Our research showed that RIT is able to kill HIV-infected cells both systemically and within the central nervous system,” said Dadachova, a professor of radiology, microbiology and immunology at Albert Einstein College of Medicine at Yeshiva University.

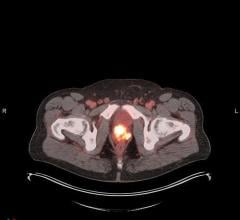

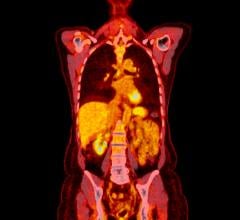

The experimental therapy may vanquish the HIV infection within the patient, she said, just as the radioactive element of the RIT – 213-bismuth – allows SPECT to track its march to HIV infected cells. Dadachova plans to use SPECT imaging to track the RIT in a clinical trial set to begin later this year in collaboration with the University of Pretoria in South Africa.

This shot at a cure may be coming none too soon. Increasingly virulent strains of HIV are showing up around the world. They are recombinants created when a person becomes infected with two different strains that fuse into a novel and more virulent form. Exemplifying the danger of such recombination is a form discovered and reported last year by Lund University in Sweden. Called A3/02, it is a cross between the two most common strains in Guinea-Bissau, West Africa — 02AG and A3.

This new strain has been found so far only in West Africa. But research has determined that recombinants are spreading globally at an increasing rate. Particularly susceptible are countries with high levels of immigration, such as the United States and Europe.

RIT is not a cure in itself but one that holds promise when used in concert with highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). Widely used to treat HIV-infected patients, HAART suppresses viral replication. But, while reducing the burden of HIV, reservoirs of latently infected cells are believed to persist in the body.

"HAART cannot kill the HIV-infected cells,” Dadachova said. RIT might.

In the research, Dadachova and her team administered RIT to blood samples from 15 HIV patients treated with HAART at the Einstein-Montefiore Center for AIDS Research. The preliminary research showed the RIT killed HIV-infected lymphocytes previously treated with HAART, reducing the HIV infection in the blood samples to undetectable levels. “The elimination of HIV-infected cells with RIT was profound and specific,” she said. “The radionuclide we used delivered radiation only to HIV-infected cells without damaging nearby cells.”

The RIT uses a type of monoclonal antibody (mAb2556) paired with bismuth radioisotope. When injected into the patient's bloodstream, the combination is expected to travel to the HIV-infected cell, which should then be destroyed by the radiation.

Raising expectations that there will be no refuge for HIV, Dadachova and her team have demonstrated that the radiolabeled antibody can cross the human blood brain barrier to reach HIV-infected cells in the brain and central nervous system. “Antiretroviral treatment only partially penetrates the blood brain barrier, which means that even if a patient is free of HIV systemically, the virus is still able to rage on in the brain, causing cognitive disorders and mental decline,” she said. “Our study showed that RIT is able to kill HIV-infected cells both systemically and within the central nervous system.”

November 12, 2025

November 12, 2025