Greg Freiherr has reported on developments in radiology since 1983. He runs the consulting service, The Freiherr Group.

How Telehealth and AI Might Amplify Human Ability

Image courtesy of Pixabay

Hospitalization adds cost to healthcare. So, keeping patients out of the hospital should reduce health costs. But how?

The answer may be found in the use of machines — not as replacements for people, as happened during the first three industrial revolutions — but in their enhancement of what people can do.

The Fourth Industrial Revolution is typically associated with the advent of artificial intelligence (AI). But impacting healthcare will take more than what AI can do alone.

In healthcare, this revolution has to make it possible for physicians and other care givers to do more. AI could be one of the needed technologies. Telehealth (aka telemedicine) could be the other.

Where TeleHealth Fits In

The imagery that is the backbone of telehealth — imagery of patients and physicians — has gotten phenomenally good, thanks to high-speed Wi-Fi networks and high-resolution cameras built into mobile devices, such as smartphones.

And fast Wi-Fi-cation has done more than that. It has made remote patient monitoring possible.

Patients who have not been in the same room with their physicians in years could stream health data to physician offices in preparation for virtual visits that could come every six months (or sooner, if the data show a problem). Before or soon after those visits, patients might drop off — or mail — blood, fecal and urine samples, for the laboratory to scan.

Smart watches can gather and send data about the patient’s heart and blood pressure. Every time a telehealth patient steps on the right kind of bathroom scale, a doctor might get the patient’s weight as well as body mass index readings.

And … voila! The future is here. Or is it?

Combining TeleHealth and AI

Telehealth and AI can be developed so that medical decision-making remains in the hands of physicians, while machines can fill in and gather information useful to making those decisions. In short, machines can make healthcare incredibly more efficient and consistent. But they probably will also make medical care more complex.

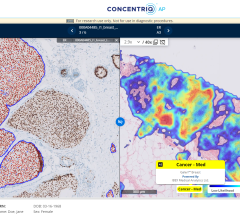

Rather than depending on three or four bits of medical information — a PSA level, prostate exam, Gleason score (determined from a prostate biopsy) and maybe an MRI — future physicians might draw from dozens of sources of information about the possibility of prostate cancer, for example. In the future, a physician might consider genomic and radiomic signatures, as well as the patient’s tolerance for impotency, as determined by analyzing responses to a questionnaire on the subject.

As they do today, physicians will make decisions based on their own experience. But their judgments might also be based on mathematically digested data describing 600 or 700 patients with similar disease — data showing how the patients were treated; the side effects that occurred; how many were cured. The patterns, as defined by smart machines, might suggest what the next steps should be.

These algorithmically determined patterns might come from data so “big” that they would elude humans, if not for the help of machines. These data, in turn, might come from the myriad of monitoring devices.

The technology for much of this is already in hand. Philips is developing AI, as are GE and Siemens; and more than a hundred other companies. GE, Philips and Siemens offer remote patient monitoring to detect problems that can force hospitalization, as do dozens of other companies. Philips has expounded on that with the acquisition of companies that have brought to it video and patient engagement software. GE Healthcare’s virtual care platform (called Mural) collects and displays vital signs, real-time video, even diagnostic images. Other companies, including Apple, are marketing smart watches to gather blood pressure, heart rate and ECG readings.

But the potential of these technologies is still far from being realized. Challenges abound. Among the most daunting are ones related to reimbursement. But they are beginning to be chipped away.

Earlier this year the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) proposed rules for the 2019 Physician Fee Schedule that would expand telehealth payment. And the federal government has invested hundreds of millions of dollars to develop telehealth. Yet, some tough issues remain.

Keeping It Simple

Ironically, keeping it simple will be … difficult. But if vendors can do so, it will pay off handsomely by minimizing the skills physicians will need to use AI and telehealth tools.

Just as automatic pinsetters made bowling more efficient, AI software that anticipates, then satisfies certain basic needs will streamline workflow. This is unquestionably so, when it comes to automating tedious and time-consuming tasks. But augmenting and amplifying physicians’ actions may require more demanding AI tools. And that could be another story.

AI must stay within the existing workflow. Which raises an interesting possibility.

Just like nurses are needed to keep the flow of work moving in a busy physician’s office, will data scientists be needed to spot trends and do the analyses that doctors will need to solve complex problems?

The trick for the makers of AI and telehealth products will be to keep their use as simple and transparent as possible. Like anti-lock braking, electronic stability and traction control have made all drivers better on slippery roads, AI and telehealth tools have to make all physicians more effective and efficient drivers of healthcare.

While healthcare AI and telehealth may indeed have a bright future, if their potential is to be realized, they must overcome human limitations without adding new burdens. To paraphrase Elton John, physicians can’t be required to understand the science in order to do their job.

And their job is to serve the patient.

August 29, 2024

August 29, 2024