Greg Freiherr has reported on developments in radiology since 1983. He runs the consulting service, The Freiherr Group.

Do Smart Algorithms Make Us Dumb?

When volumetric scanning came along a few years ago, proponents hawked the technology as a leap forward in efficiency and accuracy. Simply sweeping the entire heart would ensure the capture of every bit of data needed to make an accurate diagnosis, allowing the patient to head home, while the next hopped up on the table.

It kindled expectations of an echocardiographic nirvana with unprecedented reproducibility regardless of the sonographer’s skills, skyrocketing throughput and off-the-chart revenues. Reality has fallen a tad short.

In practice, the bottleneck once at the acquisition stage has shifted downstream to a newly created stage of image processing where the 3-D data set is carved into the views and functional data cardiologists need to form diagnoses. In many cases, this processing has fallen on the shoulders of technologists. This has snarled their schedules, reducing, if not eliminating, the time gains that 3-D acquisition was supposed to produce.

Fortunately, help is on the way.

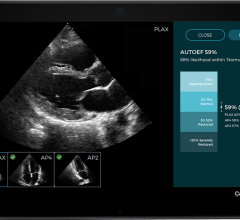

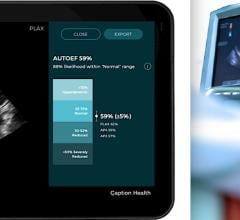

In a year or so, the first wave of smart algorithms designed for echocardiography may enter the U.S. market. These algorithms will automatically recognize and extract the data needed for diagnosis – detecting the tissues of the heart and matching them to a computerized reference model for identification; calculating volumes to reveal measures for ventricular mass, ejection fraction and wall thickness; all in a matter of seconds.

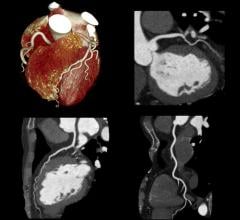

Philips Healthcare, a pioneer in 3-D echocardiography, may be among the first to offer such an algorithm. The company is working on one right now, adapting software commercialized for cardiac CT for use in echocardiography. Early results look good.

But it might be wise not to get too excited.

Software engineers have yet to write a smart algorithm that gets the answers right every time. And the one being groomed by Philips to process 3-D echo data sets will be no exception. That’s why Philips plans to include interactive tools for operators to make adjustments, when necessary.

These adjustments may be relatively rare. Preliminary evaluation of this algorithm to detect ischemic disease required corrections in just 3% of the cases.

But, while laudable for its accuracy, its less-than-perfect record underscores the fact that there will be problems that need fixing. And there lurks the great danger underlying automation.

As we become more dependent on machines, the skills needed to do the work begins to atrophy. In echocardiography, this may occur through the attrition of highly skilled sonographers, whose skills are no longer prized or rewarded by employers. Their less capable replacements may not be able to fill in for the shortcomings of smart algorithms. They might not even recognize when to step in.

It is the paradox of new technologies that the problems they solve often breed new and unexpected ones. Volumetric echo is just one example.

March 06, 2024

March 06, 2024