Greg Freiherr has reported on developments in radiology since 1983. He runs the consulting service, The Freiherr Group.

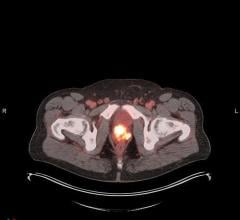

CardioGen Reveals Cardiac PET’s Soft Underbelly

Typically, the only radiation facing travelers is from the airport scanners they must walk through to board airplanes. Not so, however, for two travelers who set off radiation alarms when crossing the U.S. border earlier this month, an incident whose fallout threatens the future of cardiac PET.

Early this week the FDA warned U.S. healthcare providers to stop using the radioisotope generator commonly used to perform PET exams of the heart. Soon after Bracco Diagnostics, the maker of CardioGen-82, voluntarily recalled the cardiac generator (“FDA: Stop Using CardioGen-82 Due to Increased Radiation Exposure”).

An investigation by the FDA had found that CardioGen-82 had months earlier led to the dosing of the two travelers not only with rubidium-82, the very short half-life isotope needed for their cardiac scans, but also with strontium, a much longer lived isotope. The inadvertent dosing, according to the FDA, was due to a failure in the manufacturing process called “strontium breakthrough.”

The resulting exposure of patients to excess radiation illustrates the vulnerability of imaging devices that depend on radioisotopes. Anyone familiar with nuclear cardiology, which depends heavily on the radioisotope technetium, understands how vulnerable these devices are.

An aging Canadian reactor with a distressingly long history of shutdowns supplies the molybdenum radioisotope that generate most of the technetium used in the U.S. for cardiac SPECT studies. When this reactor shut down, spurring a 15-month technetium shortage, PET advocates – led by Bracco Diagnostics – began recruiting nuclear cardiologists to switch from SPECT to PET. (“Time for a New Normal in Nuclear Cardiology?”). This alternative, they said, was not vulnerable to such shortages. For those who were convinced, the recent news is not only ironic, but troubling.

In its warning to healthcare providers, the FDA noted that “the risk of harm from this exposure is minimal” and that “it would take much more radiation to cause any severe adverse health effects in patients.” (“CardioGen-82 PET Scan: Drug Safety Communication - Increased Radiation Exposure”) Yet estimates derived from mathematical modeling done at the Los Alamos National Laboratory indicate that exposure for the two patients may be as high as 90 mSv – more than 30 times the normal dose of a cardiac PET scan. And it is not certain that these two patients are the only ones who have been so exposed. The FDA is now trying to find out how many, if any, more patients suffered excess radiation dose due to strontium breakthrough.

One question not being asked is why this unexpected exposure was detected at a U.S. border crossing instead of the PET suites where the scans were performed. Moreover, how could such excess doses occur in the first place? Are no tests required to ensure the purity of rubidium chloride before it is injected into patients?

Toward that end, the FDA is looking into the sufficiency of the testing procedures used to detect strontium breakthrough at clinical sites using CardioGen-82. Obviously, they are not sufficient, at least not everywhere. But they will have to be soon, or cardiac PET may have a tough time recovering from a shortage that should have never been.

Editor's note: For additional information about this incident and the product recall, visit www.cardiogen.com.

November 18, 2025

November 18, 2025