Greg Freiherr has reported on developments in radiology since 1983. He runs the consulting service, The Freiherr Group.

Can Artificial Intelligence Help Against Coronavirus?

Flattening the curve. Slowing the spread. I have yet to read — or hear — anyone say we are trying to stop the coronavirus virus. To beat it. The closest has been a news commentator saying that if everyone stopped in their tracks, six feet apart from everyone else, the spread of the virus would end immediately.

Of course, that is not going to happen. So we deal with realities. We try to predict who will get the virus; make diagnoses as quickly as possible; identify who will respond to therapy. In the absence of a well-proven treatment, we want to know who has the best chance of survival and should, therefore, get a ventilator.

These are not questions to be taken lightly. Amazingly, we don’t have the answers. Any of them. It is a stunning illustration of how little we know about the future of our species and the uncertain times in which we live — humbling hallmarks of a pandemic that fell on us suddenly.

That artificial intelligence (AI) has become a beacon of hope should come as no surprise.

A Flurry of AI Reports

Since the outbreak began, there has been a flurry of reports published about how AI might help. Much of the research on which these reports are based could eventually be printed in peer-reviewed journals. One, reportedly in press at Radiology and online since March 19, 2020, describes how AI might help in the quick and accurate diagnosis of this virus.

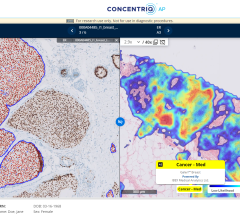

The authors of this paper describe how a deep learning algorithm can detect in chest CT images signs of the respiratory disease caused by the coronavirus and how this algorithm can distinguish it from other lung diseases, including traditional pneumonia.

Already in late December 2019, CT scans showed lesions in the lungs of Chinese patients distinct from those associated with other forms of viral pneumonia. The March 27 ITN article noted that “AI may help with both the exam process and reading of the images taken.”

Days later, the online version of IEEE SPECTRUM reported that several U.S. hospitals had begun deploying AI tools to detect COVID-19 in CT and X-ray chest scans and to monitor disease progression. According to the article, AI analysis was being used because of its “potential to alleviate the growing burden on radiologists.” In the future, the technology “might help predict which patients are most likely to need a ventilator or medication,” the article stated.

On March 30, New York University announced an experimental AI tool that predicts which patients with the virus will develop “serious” respiratory disease. Around that same time researchers reported the development of an AI “framework” for predicting clinical severity from the coronavirus. The researchers wrote that “given the increasing caseload, there is an urgent need to augment clinical skills in order to identify from among the many mild cases the few that will progress to critical illness.”

In a world awash in “worst” and “best” case scenarios (with a distinction between the two hard to discern), when the President of the United States imposes a war-time defense production order to force manufacturers like General Motors to make ventilators; when the Governor of New York says his state will need up to 40,000 of such device — efforts to identify patients who need them takes on great importance.

Chest AI

Radiology vendors have long been developing AI packages for lung diseases. AI-powered algorithms have been integrated into clinical decision support packages for the detection and segmentation of lung lesions, as well as the calculation of their volumes and diameters.

The objective has been to reduce the burden on radiologists — to shrink the time needed for these physicians to do what they must do. But the need has never been so palpable as with the coronavirus outbreak.

If ever there was a time for big data to be acquired, this is it. Picture, if you will, algorithms diving repeatedly into test data too voluminous for people to effectively analyze.

But such deep dives are imaginary. The reason? Because the big data for them does not exist. The testing kits needed to provide it are not available. Yes, tens of thousands of coronavirus test kits are being produced daily. But these are drops in the bucket compared to the 330 million people living in the United States.

The kits can barely satisfy — if they even do — the number of patients reporting symptoms and the healthcare workers who are trying to care for them, workers who lack basic personal protective equipment — masks and facial splash guards.

Global Testing

South Korea has weathered the outbreak relatively well. The government there tested many of those in the politically divided country, isolating people who tested positive alongside those with whom they associated. But the U.S. has not been able to do this — at least not yet.

Our chief infectious disease doctor, Anthony Fauci, M.D., director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, noted March 27 on National Public Radio that testing got off to “a slow start. But now we’re seeing a much more improved system with regard to its availability and implementation …”

And testing is supposed to widen substantially. The purpose, Fauci said, is to “get data to make informed decisions.” But will the data come in time to make a difference?

Every day we hear about “flattening the curve” and “slowing the spread.” Is riding this crisis out all we have to look forward to? Am I among those who will rebound from infection — or those who will die from it?

As an American, it is hard — no, it’s impossible — for me to believe that this choice is the best we can do. Fifty years ago, Americans walked on the moon! And they returned to talk about it.

If we are buying time, maybe the use of AI is what we are buying it for.

Greg Freiherr is consulting editor for ITN, and has reported on developments in radiology since 1983. He runs the consulting service, The Freiherr Group.

August 29, 2024

August 29, 2024