Greg Freiherr has reported on developments in radiology since 1983. He runs the consulting service, The Freiherr Group.

Ask What AI Can Do For You — And Your Patient

Siemens executives Peter Shen (left) and Wesley Gilson prepare to present about artificial intelligence July 21 at the annual AHRA meeting.

“It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.”

— Yogi Berra

Yogi was right. Cars didn’t fly (at least not en masse). And space stations didn’t rotate (at least not on purpose). And these are just a couple examples of technologies that didn’t happen when they were supposed to.

That doesn’t mean, however, accurate predictions couldn’t have been made. The fundamental problem was in misreading conditions.

The race to the moon in the sixties, for example, was a logical result of the Cold War. Unfortunately, politicians, astronauts — and those who wrote about them — swaddled this race in grand phrases (e.g.: “man’s reach for the stars”), raising expectations that simply couldn’t be met. This is why in 1975 the Apollo capsule rendezvoused in earth orbit with a Soyuz capsule — as a political symbol of détente between the U.S. and Soviet Union.

The second act of the space race featured space trucks — a Soviet military spacecraft called Buran and the U.S. Space Shuttle, which hauled military and nonmilitary cargoes into orbit. Buran flew once; America’s shuttles flew for decades until two were destroyed during flight and the others were hung in museums, after failing (miserably) to meet economic expectations.

How Not To Repeat History

America’s misadventures in space provide a lesson about why it is so important that we don’t expect too much from artificial intelligence. Being realistic has the power to moderate expectations. Unfortunately, realism can change. Consider the test for machine intelligence devised 70 years ago by Alan Turing, a pioneer of modern computing. Dubbed the Turing test, it contends that a computer is intelligent when interaction with that computer cannot be distinguished from interaction with a person.

Plenty of computers today could pass that test. Notably, chatbots routinely fill in for people in “customer service.” And their use could accelerate.

Does that mean that at least some of today’s computers are “intelligent?” The answer is moot.

Radiology — A Frontier For AI

“AI is here to stay for a while; maybe forever,” said Siemens’ Wesley Gilson, Ph.D., speaking to attendees of a Siemens-sponsored presentation on artificial intelligence at the AHRA meeting in mid-July.

So what is it that makes AI appealing? According to Gilson, artificial intelligence lead for Siemens Healthineers, it’s what AI might do for radiologists and patients.

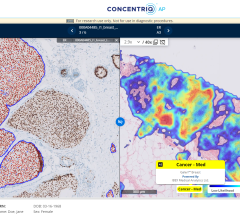

Radiology already is being challenged by the accumulation of data. Fast-growing workloads are reducing the time for interpretations, raising the potential for error. AI algorithms might help radiologists stay on top of data, he said, just as their analyses might improve disease surveillance and — ultimately — patient outcomes.

AI radiology assistants could help quantify these data and make critical measurements that improve the detection and diagnosis of disease. They might even “drive clinical treatment decisions,” said Peter Shen, vice president of business development at Siemens Healthineers. Built into machines, AI algorithms might automate workflow and accelerate the reconstruction of images.

“We want to take all this data and do something practical with it,” said Shen, who during his AHRA presentation used efforts at weather prediction to drive home the need for practicality in the analysis of healthcare data. In regard to weather forecasts, he opined that people are less interested in knowing the exact temperature than “whether they should wear flip-flops or bring an umbrella.”

“Similarly (in radiology), if we want to manage dose, we are less concerned if (a single exposure) is precisely 1.0 or 1.1 mGy,” Shen said. Operative practicality comes from changing the parameters of a CT scanner, he said, so patients get consistently less dose over time.

Gilson described how AI might automate patient positioning in CT, MRI, even mobile C-arms. Automated positioning could reduce radiation dose and enhance images, as well as save time and labor, thereby boosting productivity and reproducibility.

AI algorithms may also help radiologists and other physicians make sense of data coming from multiple sources — not only images, but laboratory and genomic information, for example. With the help of these algorithms, multiple pieces of information might be put into a customized and personalized treatment plan.

“That is where we see a lot of potential,” Shen told me after the presentation. “How can I use artificial intelligence to assess all these data and figure out how to best treat (the) individual patient?”

Eventually the data specific to a patient might be built into a “digital twin,” which could serve as a patient simulator for testing the effectiveness and safety of different treatments before deciding finally on one to prescribe. That, however, is still a long ways away, Gilson said.

Improvement Through Imprecision

The most advanced AI algorithms, the ones that come from deep learning (DL), are not mathematical constructs. Therefore, they should not be accorded the same precision as mathematics.

They get their smarts from “trial-and-error” learning, achieved often through hundreds or thousands of forays into datasets. In short, DL algorithms learn by being wrong; their experiences establish the basis for “understanding.”

While they may lack mathematical precision, they can go far beyond what can be defined purely by mathematics. This is the imprecise nature of tomorrow’s artificial intelligence, which — ironically — is modeled on human learning. It is what makes DL algorithms so potentially powerful — and potentially scary.

Some pundits have worried that smart algorithms might eventually conclude on their own that their intelligence is better than that of people. To their fear, I say poppycock … it’s like asking whether bicycles will one day outpace people in races.

Bicycles do not race. Bicyclists do. These are people who depend on machines to enhance their performance.

Similarly, machine intelligence might factor into the future of radiology … if we have realistic expectations.

Related content:

How Artificial Intelligence Might Impact Radiology

VIDEO: Technology Report -- Artificial Intelligence

PODCAST: Radiologists Must Understand AI To Know If It Is Wrong

August 29, 2024

August 29, 2024