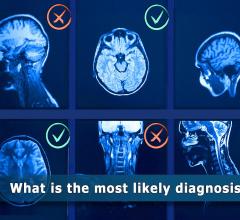

According to the GE website, these images were generated using the Mavric SL software feature and are representative of the quality of images that users should expect to generate.

Earlier this year my brother-in-law bought a pick-up truck. Its six-cylinder engine saves fuel by running on four cylinders. A computer chip fires up the other two cylinders when accelerating, then turns them off when cruising.

It’s funny how cars have changed over the years. They’ve gotten better in little ways. Like the padded dashboard that replaced the metal one that

burned my fingers after the car had been parked in the sun. And the digital clocks that replaced ones with hands that only moved when the car was on.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is getting like that. At RSNA 2012, GE brought out an MRI prototype that dramatically cut noise. Anyone who’s had an MR scan will agree that less noise is better, although personally I found I could live with it. What worried me was what I might not be able to live with — the fact that if I ever needed a brain scan, it couldn’t be an MRI.

Forty years ago half my teeth were knocked out in an accident. I got my smile back, but it took a lot of bridgework, the significance of which I didn’t recognize until I went in for a brain scan. I had thought my false teeth were ceramic. But underneath was metal, a fact made clear by the scan.

I had an enormous frontal lobe and pathetically small medulla oblongata, a finding that did not sit well with my inner lizard. If the scan had been for a medical condition, I’d have been worried. Fortunately, I was just test driving an MR scanner, one that today, I’m told, would produce much different results. The reason is GE Healthcare’s Mavric SL.

This software makes sense of data that would otherwise be twisted into nonsense by the metal implants in my mouth. Mavric SL was designed mainly for patients with knee and hip implants. The metal in these had rendered MRI useless as a diagnostic of the soft tissue damage that forces the second surgeries that are rapidly rising with the increasing use of

artificial joints.

Mavric SL might provide the early warning that can help orthopedists save implants. And, because the software reduces or eliminates artifacts caused by any metal, it clears the way for brain scans of people with imperfect mouths, such as mine.

Just as I am convinced that the impact of Mavric SL and other such improvements will be enormous, so is their value likely to be underappreciated. In the heyday of MRI, the metrics of clinical progress were obvious. They were applications that extended the reach of MRI to new turf. Swept under the rug were weaknesses in the underlying technology that we assumed were unavoidable.

Like an army rushing to liberate cities, MRI developers had looked past these weaknesses, forsaken pockets of the patient population, for example, who ended MR exams because they could not tolerate the bizarre noises or whose metal implants made MRI assessments impossible.

Noiseless MRI and Mavric SL are the results of a retroactive process, one that is redefining MRI. It makes good things better by fixing what we didn’t know could be fixed or didn’t recognize needed fixing. It is how mature technologies advance. And it is how we will tell that MRI and other forms of medical imaging are progressing in the future.

To see where it will take us, we need look no further than the vehicles we drive.

Greg Freiherr has reported on developments in radiology since 1983. He runs the consulting service, The Freiherr Group.

Read more of his views on his blog at www.itnonline.com.

August 06, 2024

August 06, 2024