Image courtesy of Carestream.

Annual breast cancer screening is a chapter many women are hesitant to add to their personal medical history books. Undergoing frequent mammograms and other imaging exams means growing that mid-life medical history, often in a complicated way. In breast health, access to prior exams is critical in determining if and how the images have changed. Radiologists and other specialists — typically at separate locations — require access to a detailed patient history in providing optimal, safe care. Patients, too, must be proactive about their own screening and care decisions, especially considering risks of radiation dose and other clinical treatments.

Accountability in today’s healthcare climate means guaranteeing the best patient outcomes from the available information we have about that patient. Unfortunately, current health care systems struggle to communicate and integrate their processes for targeted care coordination. Disjointed systems and workflows mean that primary care providers, radiologists and other specialists are often not on the same page of this very detailed book, “Your Patient’s Medical History.” Specialists may not be fully aware of why certain exams are being ordered; referring physicians may not receive results in a timely manner (or at all). Patients are overwhelmed with the barrage of doctors’ recommendations, office policies, insurance protocols and decisions to make.

Despite all of our knowledge and expertise, inefficient care is plaguing the healthcare system. Targeted care coordination via well-designed workflow, proactive communication and the most modern information-sharing technologies must take center stage to track and support medical history.

Accountable Care

Value-based care is more important than ever. Providers are striving to provide better outcomes and improved patient experiences. Breast cancer screening and treatment are highly sensitive specialties where patient needs and wants must be considered and vocalized. The patient plays a very important role in her own outcomes through the seeking of proactive and preventive care, and navigating this care. It requires detailed coordination among the primary care practices, imaging centers and specialists through the sharing of results and patient history. A woman who first has a mammogram then receives a breast cancer diagnosis may ultimately work with some combination of radiologists, medical and surgical oncologists, breast and plastic surgeons, radiation oncologists and other healthcare providers — all of whom must share patient images, results and progress.

Following the initial screening process, the patient must also take an active role in considering and outlining preferences about treatment, including psychological treatment to assist with well-being. Every woman must weigh the medical facts with personal preferences regarding nipple preservation, mastectomy, double mastectomy, possibly surgical reconstruction, chemotherapy and other emerging treatment options. Her wants and needs should be communicated to the right people at the right times, and healthcare providers must be listening with the totality of the patient case at their fingertips.

Achieving care coordination requires a forum for free patient-centered communication, teamwork and health information technologies to facilitate information sharing. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality suggests care coordination activities that include:1

• Establishing accountability and agreeing on responsibility;

• Communicating and sharing knowledge;

• Helping with care transitions;

• Assessing patient needs and goals;

• Creating a proactive care plan;

• Monitoring and follow-up as needs change;

• Supporting patients’ self-management goals;

• Linking to available community resources; and

• Working to align resources with patient and population needs.

Image Availability

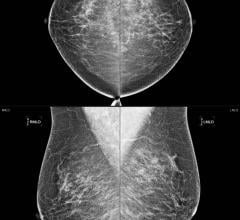

As radiation dose concerns have grown in recent years, so have concerns about mammography. Current mammography units give off small amounts of radiation, but women may still feel compelled to discuss the test with their physician in regard to risk versus outcome, family history and personal breast composition. Physicians, of course, may recommend that women with dense breast tissue have an ultrasound or breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Patients should ask their doctors if they need the exam, and how it will improve their health. They should discuss alternatives (if available) and which exams will bring maximum benefits.

In an ideal scenario, the radiologist will find nothing suspicious on the patient’s mammogram and the patient will return in one to two years, depending on age. It’s also ideal that the radiologist reading the mammogram has compared it to the patient’s previous results. The films do not stand independently; the appearance of tissue or masses may change from one year to the next in size or shape. So the more priors the interpreting radiologist has access to, the better the detection rates for abnormalities.

In seeking the highest possible detection rates, the prior and current exams need to get in the hands of radiologists specially trained in mammography interpretation. For small centers, this may mean outsourcing reads to outside groups that specialize in the modality. Working with off-site readers adds some complex considerations to the process. The images need to be transmitted, where they often sit in a queue waiting to be read. The patient may be waiting for results to find out if she needs an additional exam or further work-up. Even the interpreting radiologist’s transcription and report process may be incongruent with the center’s workflow, placing expeditious results rendering in jeopardy.

Thankfully, radiology and health IT have developed solutions to workflow “hiccups” in the transmission and interpretation of medical images. Current zero-footprint technology only requires a Web browser, no downloads, plug-ins or installations for full-functionality performance and image review. Various practices can use their own separate radiology information system (RIS)/PACS, software and hardware, and incongruences are a non-issue. Communication with outside groups and subsequent reading and review are made simple and seamless.

Similarly, server-side rendering enables “anywhere, anytime” reading for maximum efficiency and timeliness. Large files with prior images can be accessed quickly without prefetching, meaning bandwidth speed issues do not create unfortunate bottlenecks, which benefits radiologists, imaging centers, referring physicians and the patients themselves. DICOM datasets will never have to be pushed down to the workstation, yet the complete diagnostic package is available for interpretation that brings flexibility and value. Tools to accommodate various systems, complex data demands and reports include custom dashboards and workflow engines that allow radiologists to view the information, create reports and optimize workflow based on what is most critical to them.

Also considering the need to drive value in care provision, current tools also offer business intelligence and analytics dashboards for optimizing operations. For centers that outsource mammography reads to specialist radiologists, administrators can track turnaround speeds for reports, zeroing in on the most efficient interpretations. For a center with significant volume, this translates to intelligent allocation of resources on top of offering patients the most clinically experienced interpretations of their mammograms.

Seeking value and care coordination clearly requires integration at various stages of the screening and diagnostic process, starting with image interpretation. From a multidisciplinary perspective, it further strengthens radiology’s critical role in the team management of patient care. Consider also the significance of downstream integration: returning to initial findings and interpretation to track progress and make educated treatment decisions. The future of RIS/PACS may certainly lie in improving overall outcomes for all patients, especially breast cancer patients.

Patient Empowerment

If and when various disciplines are added to the treatment plan, patients need to take personal responsibility for ascertaining and sharing their medical histories with physicians. Patient portals have brought patient engagement into the mainstream. Over the last decade, electronic medical records (EMRs) have provided a means to digitally store, and often share, patient data. Now, personal health records (PHRs) allow patients to build secure online medical history files they can supply to providers of their choice, including medical images.

RSNA Image Share has made it easy for radiologists to share medical images with patients using the PHR accounts. Funded by the National Institute for Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB) and administered by RSNA, patients are using the pilot project at medical centers nationwide.

It seems we have finally entered the era where technology can provide the coordinated care tools that are required for improved, targeted outcomes. And physicians, providers, payers and patients are on board.

Reference

1. www.ahrq.gov/professionals/prevention-chronic-care/improve/coordination…, accessed March 22, 2016.

Steve Deaton is the vice president of Viztek, a Konica Minolta company.

July 29, 2024

July 29, 2024