Four short years after the nation’s first Breast Density Inform law was fought for and enacted in Connecticut, the grassroots movement by patient advocates has resulted in a tidal wave of legislation that shows no signs of abating. As of this writing, 11 states now have mandatory Breast Density Inform legislation: Connecticut, Texas, Virginia, New York, California, Hawaii, Maryland, Tennessee, Alabama, Nevada and Oregon. The 2013 state legislative sessions gave rise to 19[1] new bills, meaning half of the country now either has or has drafted breast density notification legislation.

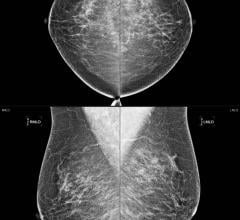

Legislative efforts have been bolstered by research confirming breast density’s masking effect on mammography and the more recent acceptance of breast density, in and of itself, as an independent risk factor for the development of breast cancer. On point, the American Cancer Society’s publication, “Breast Cancer Facts and Figures 2011-2012,” cites breast density as a greater relative risk factor than having two first-degree relatives who have had the disease. This past March, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention followed suit adding “breast density” to its list of “Risk Factors” for the development of breast cancer, and Susan G. Komen’s Breast Cancer Risk Factors Table now links “high breast density” with a “strong increase in risk” of breast cancer.

Breast Density a Relevant Consideration

Women with dense breasts are more likely to get breast cancer and more likely to have that cancer missed on a mammogram; a life-threatening double whammy. Further, research published in 2011 by Jack Cuzick et al.[2] found that women on tamoxifen who experienced a reduction in breast density of at least 10 percent had a 63 percent reduction in breast cancer risk, while women who experienced less than a 10 percent reduction in density did not experience a reduction in risk. It would appear that breast density is a relevant consideration at every step of a woman’s breast health surveillance — from screening through treatment.

In light of these developments, it is not surprising that breast density is a frequent fixture in the news: from a specific modality’s ability to detect cancers in dense breasts, to new software that quantifies breast density; and from news that specific survival may be associated with a decrease in breast density, to research as to why dense breasts predispose to metastasis. As this information filters into the public consciousness, and as women become more aware of the inherent risks of dense tissue, the patient chorus for density notification has gained great support — and for good reason. It is clear that additional cancers will be found if women with dense breasts are sent for supplemental screening.

The 21-center ACRIN 6666 trial, led by Wendie Berg, M.D., Ph.D., professor of radiology at University of Pittsburgh, Magee-Womens Hospital, funded by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and Avon, and published in JAMA in 2012, demonstrated that adding breast ultrasound to mammography in women with dense breasts increased cancer detection by 5.3 per 1,000 women in the first year, and 3.7 per 1,000 women each year thereafter. Ninety-four percent of cancers found only with ultrasound were invasive, and 96 percent of those were node-negative. With mammography, it is known that the detection of node-negative invasive cancer can save lives; ultrasound screening is expected to have similar benefit, but this is not known. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was far more sensitive than even combined mammography and ultrasound, identifying another 15 cancers per 1,000 women screened in a substudy. Such results validated many single-center trials of ultrasound and both single-center and multicenter experience in high-risk screening MRI.

Studies conducted in Connecticut after the enactment of the state’s Breast Density Inform law in 2009 corroborate the benefit of supplemental ultrasound screening in normal risk women with dense tissue and negative mammograms. One study states, “Recently, two Connecticut-based groups published the first post-legislation outcome studies, which both demonstrated that ultrasound screening in women with dense breasts detected an additional 3.2–3.25 breast cancers per 1,000 women, double the number found with mammogram alone.”[3] When Connecticut’s supplemental ultrasound find rate is applied to the screening population in my own state, New York, it is estimated that annually at least 2,500 women with dense breasts leave their mammograms being told all is “normal/negative,” but actually having invasive breast cancer that would be found if these women were sent for screening ultrasound examinations. Nationally this extrapolates to an estimated 40,000 women per year.

The Right to be Informed

In 2010, a Harris Interactive poll found that 95 percent of women did not know their own breast density; however growing public awareness about breast density and Breast Density Inform laws is changing that. There is no shortage of women who were not told of their own breast density, no shortage of women with cancers found at a later stage than necessary due to tumors obscured behind dense tissue and no shortage of women seeking change.

The most comprehensive Breast Density Inform laws have been enacted in New York, California, Hawaii, Tennessee, Alabama and Virginia (whose 2012 law was amended in 2013). Based on the American College of Radiology’s own suggested “density notification” letter, women receiving notification in these states are told in clear unambiguous language that their breasts are dense. It states dense breasts are not abnormal but can interfere with the effectiveness of their mammogram, may be associated with an increased risk for breast cancer and refer them to their doctor to discuss risk factors and the benefit of further screening. These letters, designed to raise awareness and complement a conversation with their doctors, give women a starting point for discussion and self-advocacy.

Though some Breast Density Inform laws are more similar than others, there is no consistent inform language utilized by states that enact laws. Furthermore, each additional state drafting legislation promulgates its own bill language. Bill variations run the gamut from who gets the density notification (sometimes all women, sometimes only those with dense tissue), varying degrees of notification (“You HAVE dense breasts” vs. “IF you have dense breasts” vs. “Your mammogram indicates you MAY have dense breasts”), varying specificity about supplemental screening (sometimes ultrasound and MRI are mentioned, sometimes the generic term “more screening” is used), to inconsistent mention of density as an independent risk factor for breast cancer development.

Uniform and Standardized Regulation for Mammography

Every state that drafts a bill adds a potential new variation to the mix. As a result, women living in neighboring states may get very different density notifications. This inconsistency in mammography result reporting is precisely what the Federal Mammography Quality Standards Act (MQSA) was designed to prevent. The goal of the MQSA is to ensure uniform and standardized regulation for mammography and for mammography reporting, to “improve quality and seek excellence while giving women the information they need to make better-informed healthcare decisions.”[4] Clearly, a national requirement for standardized breast density notification is necessary to rectify this growing inequity and it would seem best accomplished through a MQSA directive.

With the goal of universal breast density notification for all women, after state level efforts on New York’s bill, I pursued initiatives at the federal level. Efforts for an MQSA amendment to require inclusion of breast density information in the patient “lay” letter as well as a federal bill were initiated in 2010; the latter of which, the Breast Density and Mammography Reporting Act, had 45 co-sponsors last Congress and is scheduled for a 2013 reintroduction to the House.

National Standardized Notification

U.S. women, no matter which state they call home, deserve to be equally informed about their own breast density and its inherent risks. To date this charge has been led in state efforts by cancer fighters and survivors who learned the risks of their breast density too late. An MQSA amendment to require the inclusion of breast density notification in both the patient “lay” letter as well as the report to referring physicians is necessary. The time has come for national standardized breast density notification.

JoAnn Pushkin is a two-time breast cancer survivor and Breast Density Inform advocate. She is co-founder of D.E.N.S.E. (Density Education National Survivors’ Effort) and founder of D.E.N.S.E. NY. You can contact her at Dense-NY@optonline.net.

References

1. Ala., Fla., Ga., Hawaii, Iowa, Ill., Ind., Mass., Md., Mich., N.C., N.J., Nev., Ohio, Ore., Pa., S.C., Tenn., Va. (amendment)

2. Cuzick, Jack, et al. “Tamoxifen-Induced Reduction in Mammographic Density and Breast Cancer Risk Reduction: A Nested Case-Control Study.” J Natl Cancer Inst 2011; doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr079.

3. Brower, Vicki. “Breast Density Legislation Fueling Controversy.” J Natl Cancer Inst 2013; doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt086. First published online: March 22, 2013.

4. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Mammography Quality Standards Act and Program. www.fda.gov/radiation-emittingproducts/mammographyqualitystandardsactan…. Accessed June 3, 2013.

July 29, 2024

July 29, 2024